During our chat, he shares how his university is eliminating the opportunity gap through a commitment to affordable and accessible education.

I’ve had the pleasure of hearing your 4‑H story. For those who haven’t, can you share your 4‑H experience and describe what it was like for you in your community?

Dr. Robert Jones (RJ): I was encouraged to join 4‑H in elementary school. It was probably the first structured and informal learning environment that I participated in outside of school and church. I do remember our 4‑H chapter met on the top floor of a funeral home, which was pretty traumatizing for me. And although this was in the Jim Crow South—only the Black kids met together—it was a good experience for me. That positive youth development helped me better understand myself and my leadership capabilities.

How was your 4‑H experience different from today’s 4‑H?

RJ: The idea of youth development, leadership development, and character building are still very much at the core. But how that mission is delivered, I think, has transformed significantly. I think there’s been a deliberate effort to extend this youth development program, through Cooperative Extension*, to more urban communities and communities of color. I think it’s one of the things that has changed dramatically, in addition to the use of technology, particularly during COVID-19. I am delighted that 4‑H continues to carry out the mission of education and training, leveraging technology and innovations. So, while the core mission remains the same, 4‑H’s mission is actualized and the strategies for delivery have changed significantly.

As mentioned on the university’s website, you’re helping to make “world-class college education affordable and accessible.” Why is that so important?

RJ: Affordability and access are things that I have been very adamant about throughout most of my academic career. Because of my father—who made sure we didn’t miss school to harvest crops—I’ve always understood the value of an education. I think it was W.E.B. DuBois that said something like, “There’s nothing more fundamental or more critically important than the right to an education.” I embrace and invite that notion throughout my life. My parents couldn’t afford to send me to college, so I had to work two full-time jobs to make enough money to pay my first year of college tuition. I had to work to provide access to my own education and my goal is to try to make it easier for others.

Besides your father, was there someone in your life who had a similar passion and invested in you the way you invest in young people today?

RJ: I call them interveners: those who protect you from yourself. The first one in my life was my vocational agriculture teacher in high school. He took me under his wing and encouraged me to get involved in different programs. When I attended Fort Valley State University, there was Malcolm Blount, who was in charge of undergraduate education for all the Agronomy Science students. He set very high expectations. Lastly, while in the Ph.D. program at the University of Missouri, there was Jerry Nelson. He prepared me for a life as a university professor and a successful scholar and scientist. He nominated me for the George Washington Carver Scholarship that made a financial difference in my own accessibility and affordability of education. These were the folks along the way that helped make a difference.

During your tenure as Chancellor, you’ve spearheaded many of the university’s efforts in expanding diversity within the school’s programs and opportunities within the community. Share some of the university’s successes in closing the opportunity gap.

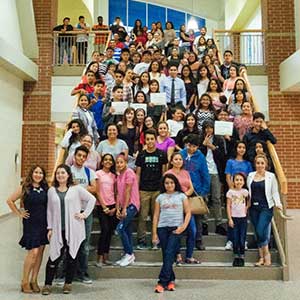

RJ: We have almost 10,000 international students. However, we struggled a bit with increasing the diversity of the student body. So, we were able to create the Illinois Commitment, which offers free tuition and fees for any in-state student from a family making $61,000 or less to provide access to the university experience. As a result, we brought in the largest cohort of African American and Latinx students in the university’s history. We had a 7.2% increase the first year. It’s a big financial commitment to do that. But, nothing’s free; somebody has to pay this commission. So we decided that we would pay it. It has been one of the most transformative things I’ve been able to do at a university. And in a financial crisis caused by the pandemic that’s costing us over $200 million so far, we made a commitment to continue advancing access and affordability.

How did the university’s work shift during a global pandemic, and how is it continuing to evolve?

RJ: I’m proud to say that we were one of the first institutions to move to remote education. But we were hearing from our students and their parents that they wanted to be back on campus. We knew that the best educational experience you can offer students is a face-to-face model. So, we decided on a hybrid model to start the fall semester, with about 30% of our courses in-person. To make this happen, we needed to conduct tests at least twice a week, and the nasal test is very uncomfortable. It was evident to us at the time that the available COVID-19 testing capability was not going to be congruent with our ability to bring nearly 50,000 people back to campus. So, as one of the top institutions receiving funding from the National Science Foundation—allowing us to continue advancing research during the pandemic—we did what Illinois does: we invented our own test! Our saliva-based COVID-19 test is the most innovative in the world. It’s scalable, cost-effective, and it is the main reason we could complete the fall semester the way we started.

Now, over 50 universities are using our test or taking an interest. There’s potential for implementation in Seoul, New Zealand and Indonesia. We’ve even had conversations with the Biden Administration. So, what we developed for our own selfish purposes to bring our students back on campus has turned into a testing ecosystem.

Your overall commitment to putting your students first is admirable. How can more universities close the opportunity gap and create more equitable experiences for young people in all stages of their learning/careers?

RJ: As leaders in higher education, we should be concerned about the educational experiences of students on campus, and work with K-12 education to ensure more students are college-ready. We have to take some ownership of the fact that the percentage of students of color graduating from high school is going down. The percentage of students of color that are college-ready is only a fraction of what it was 10-20 years ago. So I can’t sit here creating multimillion-dollar programs to provide access and affordability for students when there is a decreasing number of students that are going to be qualified to take advantage of these opportunities. We need to be more intentional and strategic to ensure kids are reading by third grade, doing math by fourth grade, and college-ready by ninth grade. We need programs like 4‑H, which provides essential youth development resources, mentors and hands-on experiences for life, college and career readiness.

*The Cooperative Extension System is a nationwide, non-credit educational network. Each U.S. state and territory has a state office at its land grant university and a network of local or regional offices. These offices are staffed by experts who provide useful, practical, and research-based information to agricultural producers, small-business owners, youth, consumers, and others in rural areas and communities of all sizes.

Nationwide, the Nationwide N and Eagle and Nationwide is on your side are service marks of Nationwide Mutual Insurance Company. © 2021 Nationwide