I reminded him, “You can call your 4-H leader or the friend who gave you the chickens. You can also call the farm supply store. They will be able to answer your questions, and then you will know what to do.”

So he would call them for advice – a lot – and learned a lot in the process. When the chickens got mites, he learned to give them a dust bath with a special powder. When they were losing their feathers and not laying eggs, he discovered the chickens were molting. He learned to put apple cider vinegar in their water to keep away respiratory illnesses. He fed them crushed oyster shells to make their egg shells stronger. James learned to their personalities and noticed when one was acting “broody” or trying to lay an egg. He also learned the different “calls” they would make to each other. James enjoyed watching their daily routine of eating grubs and grass, scratching and dust bathing in the dirt and laying eggs. He took care of them. He played with them and talked to them. They were his pets; he loved them.

James decided to add to his flock and ordered six chicks at the farm supply store. He set them up in the basement in a brooder with a heat lamp to keep them warm. He finally had chickens in the house! However, after two weeks, he found one of the chicks lying motionless. The chick had died. It just wasn’t strong enough to survive, and it was very upsetting to James. The other five chicks thrived in the basement for three months, while James worked to expand his handmade coop, hoping to make room for the new chicks.

Quickly, the baby chicks grew, and by the summer there were eight chickens in the coop. It took some time, but eventually, the older girls accepted sharing the coop with the chicks. That, however, was the least of James’ worries, as a coyote scare threatened the lives of the chickens. One day, a coyote came around the coop stirring up the chickens. It even tried to attack one of them through the wire. James worried about them getting hurt or even worse – killed! His worry and fear for the safety of his chicks fueled his determination to make the coop safer and more secure, working tirelessly with his dad.

Suddenly, fall arrived and they stopped laying eggs. Winter soon followed and was even colder than the last, and it seemed like spring would never come. But at last, they started to lay eggs once again. James sold his eggs to his teachers at school and earned enough money to pay for their feed.

Goldie was no longer laying eggs, but she was fun to have around and always up to some mischief in the coop. One day James went out into the coop with a bag of treats and Goldie jumped up at the bag of meal worms he was holding, and she grabbed them right out of his hands! She ate it all, leaving nothing for the others.

“Silly Goldie!” James laughed.

Once summer arrived, James was able to participate in the local agricultural fair with his 4-H group and show his Bantam chicken, Lily Bell. He placed third in Showmanship and Knowledge among dozens of kids. James was the only kid in his club to place, judged by the toughest judge to ever be invited to the fair – so the organizers told us! James has this confidence whenever he can talk about his interests, so this came naturally to him. All his time researching chickens had earned him a third place ribbon at the fair. We were so proud of him, and it was nice that the kids from his club were all happy for him, too.

How do we strengthen the connection between family and youth development? It’s with various in-school and after-school programs that 4-H is able to not only contribute to the upbringing of today’s youth, but to encourage greater family engagement. The work of 4-H is beneficial to all involved—youth, parent/guardian and adult leader/mentor.

So, what organization knows the importance of youth and family engagement better than the National Parent Teacher Association (PTA). In celebration of National PTA Founders’ Day, we were honored to chat with the National PTA president and 4-H alumnus Otha Thornton.

“[Serving people] was the core of 4-H to me,” he says, recalling the third H—pledging his hands to greater service.

During his five-year involvement with 4-H, Thornton participated in a number of programs, including gardening, photography and canning, with his photography skill earning him an award for what was a personal hobby of his.

Thornton went on to receive his bachelor’s degree in urban planning from Morehouse College and received his master’s degree in communications from Michigan Technology University. He also served in the United States Military and is now a retired United States Army Lieutenant Colonel. Aside from his role as National PTA president, Thornton currently works as an operations specialist at General Dynamics.

We caught up with Otha Thornton to get his insights on today’s 4-H and how he feels its values are helping to empower youth in varied communities across the country.

How do you think 4-H is helping develop youth today?

Otha Thornton (OT): I believe 4-H is developing youth now through the importance of service in the community, through the importance of being healthy adults and also developing leadership skills. Youth are given so many opportunities to develop their leadership skills through 4-H.

Tell us about other interests you gained because of skills developed in 4-H?

OT: When you’re in 4-H, you’re exposed to so many different things and exposed to different people. That, for me, was very important. I also think about the four H’s: Managing and thinking (Head); Relating and caring for people (Heart); Giving and working (Hands); Living a healthy lifestyle (Health). Those values help. They really make a difference.

Today, 4-H is focused and committed to serving youth in all backgrounds, including those in urban communities. What challenges do you see these youth facing today and how do you think 4-H can play a part in solving these issues?

OT: I think what is critical is empowering our youth to reach their full potential. It’s important to partner with communities and continue to give kids opportunities, especially in the urban communities. I know 4-H is strong in our rural communities, but it’s also in the urban communities where 4-H can really make a difference.

With your military background, how do you think military families and youth benefit from the 4-H Military Partnerships?

OT: I believe 4-H work with children in military families benefits them by reinforcing positive physical and mental development. One thing I know 4-H offers is mentoring programs. These are the sort of programs that work really well for the military and its partnership with organizations like 4-H. Mentoring is really important in the positive development of military youth.

What does it take for families to become actively involved in a child’s learning and upbringing, both during and after school?

OT: One of the things PTA is working on, which is an element of what 4-H is doing, is promoting the importance of health and healthy lifestyles. PTA has great programs that promote healthy lifestyles as far as education. We’re working very closely with communities across the country to help put an emphasis on early childhood education. Encouraging healthy lifestyles is what will make our kids more productive and more competitive in the country and the world.

What is top priority for National PTA right now?

OT: PTA is now leading in family engagement. We’re working with the secretary of education, we’re working with Congress, and we’re working with folks all around the country to find ways to get more families involved in education. They estimate that when you invest in a kid in education, that’s almost equivalent to $1,000. We want to get all family members in every family engaged. The bottom line is when you get involved, kids do better in school and it opens up more opportunities for them and their lives.

Do you think the importance of family engagement is prevalent in the work of 4-H?

OT: Absolutely! The mission of 4-H is to empower youth to reach their full potential through working and learning with the help of partnerships with caring adults. That contributes to family engagement.

How do you think 4-H is helping to build towards its vision of growing more youth leaders and preparing them for leadership roles as an adult?

OT: I believe what’s most important is the values 4-H encourages. It teaches kids how to manage and how to think. The organization also stresses the importance of being able to relate and genuinely care for people and make a difference. Giving back to the community and working to make them better is also a crucial value. Lastly, 4-H is teaching youth about being healthy and living the healthy lifestyle that will make a difference in their lives and being better, more productive citizens. These are very important values that 4-H provides to strengthen the leadership skills of youth.

James was an energetic but sensitive young boy growing up the middle child of three boys. Although he struggled in school and had social difficulties, we provided him with support in school and at home. James had a hard time making and keeping friends, because of struggles with social perceptions. Most kids just didn’t understand his interests, and he found it hard to connect with them. He always felt like the kids just didn’t get him and didn’t want to be his friend. From about third grade he wasn’t invited to birthday parties and struggled in team sports. He had a lot of creative energy, so he spent a lot of alone time developing his train modeling hobby and kept busy doing projects and building things.Since he was a little boy, James had always been fascinated with chicks and chickens. When James was in first grade, his class hatched some eggs in an incubator loaned from the local county 4‑H Extension office. The baby chicks were so soft and fuzzy, and he loved hearing their little ‘cheep cheep’ sounds.

James was an energetic but sensitive young boy growing up the middle child of three boys. Although he struggled in school and had social difficulties, we provided him with support in school and at home. James had a hard time making and keeping friends, because of struggles with social perceptions. Most kids just didn’t understand his interests, and he found it hard to connect with them. He always felt like the kids just didn’t get him and didn’t want to be his friend. From about third grade he wasn’t invited to birthday parties and struggled in team sports. He had a lot of creative energy, so he spent a lot of alone time developing his train modeling hobby and kept busy doing projects and building things.Since he was a little boy, James had always been fascinated with chicks and chickens. When James was in first grade, his class hatched some eggs in an incubator loaned from the local county 4‑H Extension office. The baby chicks were so soft and fuzzy, and he loved hearing their little ‘cheep cheep’ sounds.

James came home from school and asked me, “Can I have a baby chick? They are soooooo cute.” I replied, “Well what are you going to do when it grows up to be a BIG chicken and it’s not so cute anymore?”

Although I could see his eagerness, I had to refuse his pleas.

Years went by, and James would occasionally ask if he could get a chick but I still declined, telling him he would have to settle for visiting them at the farm supply store. Neither my husband nor I had any farming experience growing up, so we were hesitant to indulge him with this. It was also difficult for me knowing he was excluded from social activities with peers. It made me angry that kids didn’t include him in their invites and the parents that I was friends with did not see that he was invited. At times he would come home and say everyone in the class was invited to the party accept him. He would over dramatize the real situation because that was how he felt. It was heartbreaking, but it left him lots of alone time to develop his interests.

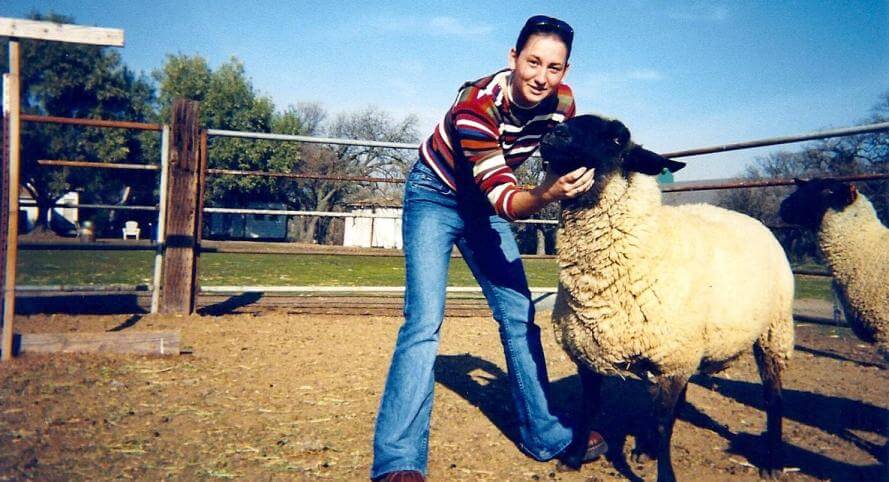

That summer, James worked at an organic farm during the summer program that was offered at his school. He helped out with coop chores and gardening. Then his persistence kicked in.

James: Mom can I get a chicken?

Me: Are you kidding me? What are we going to do with chickens? No!

James: Yes! They lay eggs, so they earn their keep. They even make chicken diapers so they won’t poop all over the house and they make great pets!

Me: Chickens in the house? No! I don’t think so.

James: But I really want some chickens! They are so funny and I know I can take care of them. I can even build a coop!

James didn’t understand why we wouldn’t let him have chickens. James was always very persistent with his interests. He always had to have things right when he wanted them, or a meltdown would ensue. It is hard to manage the urgency he always brought with his enthusiasm, and I thought it was me who would have to take care of those chickens. I wasn’t ready to take on anything like that.

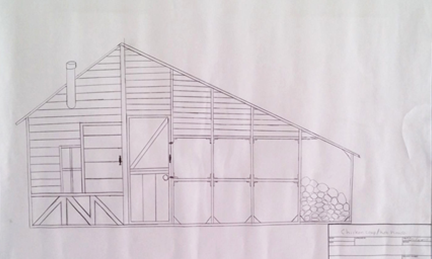

One day after the new school year started, James came home with chicken coop plans he had designed on special blue print paper his teacher gave him. The details were amazing. It had a hen house and an enclosed chicken run to keep them safe. He had spent countless hours on the computer searching every thing he could learn about building a coop. He found out about providing roosts so they could perch to sleep, how big he should make the coop, how to secure chicken runs from predators to protect the flock. He also researched how many nesting boxes were needed for laying eggs. He would talk to anyone who knew anything about chickens. He asked so many questions that he became a chicken boy expert! Every day he would try to convince us that he could raise chickens. He drove everyone nuts with all the chicken talk! We were beginning to think that maybe getting chickens wasn’t such a bad idea.

His therapist told us that with his keen interest in chickens that perhaps joining a 4‑H club could give him a sense of community and belonging that he wasn’t able to find with peers at school. He would also be around people that had the same interests as him! This helped persuade us to believe that he could do this.

“OK,” I finally said, “you can have some chickens, but you will need to join a 4‑H club and meet other people who have chickens. If you have any questions or problems, you can call them. But if they get sick you’ll have to give them back to the farm.”

We didn’t have the money for a vet, and I worried that James just wasn’t able to manage that because he didn’t have a lot of experience dealing with sick chickens yet. He was anxious and worried about this, so I felt it was better that he have a choice to take them back to the farm.

So James built his coop with help from his dad and big brother. He built it to look just like his drawings.

He joined a local 4‑H chicken club that had lots of kids and adults who loved chickens just as much as he did, and he made lots of new friends. He went to 4‑H meetings and school, and in his spare time, he built his coop. It took him three months, but finally, the coop was ready for chickens. We had checked out a couple of local clubs in fall of 2012 and chose the one that had some boys in it. It was called United Bantams. He was the oldest member of the club at age 13, and the other members looked up to him and offered their friendship and support almost immediately. James was also voted the president of his club because he knew so much about chickens and would answer anybody’s questions including the club leaders! For the first time in a very long time, he had friends and felt like he belonged.

It’s so easy to forget the meaning of words that we often recite. I’m no different; as a lifelong 4-H'er, I’ve recited the 4-H pledge too many times to count. I’ve literally gone through the motions of the pledge. At every meeting and gathering, we pledge parts of ourselves for the good of the whole, which is something radical in our often too individualistic society. The first time I heard the 4-H pledge at a meeting in rural Jamaica, I was struck by how meaningful these words really are.

It’s funny. After my 10-year 4-H career ended in America, I always knew I’d be involved in 4-H in some capacity, as a volunteer leader or livestock judging coach, but if Peace Corps service has taught me anything, it’s to expect the unexpected. Never in my wildest dreams did I think I’d be teaching rural Jamaican youth about water conservation, how to compost, select cattle, or knit, all as part of 4-H.

4-H began in Jamaica in 1944, even before the country gained its independence from the United Kingdom in 1962. The role of Jamaica 4-H has changed and evolved through the years, but it is currently the “youth arm of the Ministry of Agriculture.” Jamaica 4-H seeks to get youth more involved in agriculture, an extremely important task as the average age of a Jamaican farmer climbs every year. We also encourage sustainable agriculture practices, like composting and rotational planting, to combat the deeply felt impacts of climate change.

But for me, 4-H has provided a little continuity amid the cultural confusion. Familiar things like the 4-H clover, the pledge and the motto comfort me when I see them every day. Jamaica 4-H is still very traditional by American standards, though. Craft projects and “conventional” agriculture remains the largest part of our mission. I’d love to see Jamaica modernize in the future! Like many social programs in developing countries, Jamaica 4-H faces budget shortfalls and many times we simply don’t have the money to do some programs. So we make do with recycled crafts, donations and support from local businesses. With donations from some of my 4-H contacts at home, we were able to make a set of 4-H pillows and have stickers and balloons for fundraising and marketing, invaluable because you can’t find 4-H merchandise down here!

4-H's mission is so universal, so important to youth and agricultural development that I often wonder why it isn’t a bigger part of US foreign policy. Here in Jamaica, 4-H gives rural youth the opportunity to learn about sustainable agriculture, citizenship, microenterprise, and the natural world around them- subjects that aren’t ordinarily taught in school here and will be critical in Jamaica’s development.

Jamaica has a deserved reputation for beautiful beaches, jerk chicken and great coffee, but my year and a half of Peace Corps service has taught me that there is so much more to this tiny Caribbean island. There is desperate poverty just outside of the fancy all-inclusive resorts. But there is also an incredible spirit and hope among Jamaicans. They are thankful every day for what they have and always have a song in their heart. My hope is that Jamaica 4-H touches lives and allows those youth to lift themselves out of the vicious cycle of poverty.

We continue to share the amazing stories of adults who credit their experience and life lessons learned in CLOVER for influencing their lives and careers today. In this month’s Alumni Spotlight, we feature Ph.D. candidate and former California CLOVER’er Ariel Rivers.

Ariel’s 10-year involvement in CLOVER has inspired a life in agriculture. Currently, she is a Borlaug Fellow in Global Food Security for Pennsylvania State University’s College of Agriculture Science. She has previously worked in various positions within the Cooperative Extension System and agriculture sector: as an intern in Yolo County, California; as an AmeriCorps member in Clark County, Washington; and as a researcher at Pennsylvania State University in Centre County, Pennsylvania.

“In our county, we were required to be in the county-wide leadership project to serve on [camp] staff,” she explains, “and it was in that project that I cultivated many of my lasting friendships. I attribute a lot of the development of my personality to camp, as well.” Ariel notes that it was at camp, specifically, where she was challenged to explore, socialize, be creative, and learn about her environment.

Today, Ariel says it was the constant collaboration enforced in CLOVER that defined her personality as an adult.

When it comes to the life lessons she has learned, Ariel refers back the 4-H Pledge.

“I think the 4-H pledge is permanently instilled in me,” she says. “I am currently a doctoral student in Entomology and International Agriculture, studying sustainable agricultural systems and the conservation of insect and spider biodiversity. One has to think clearly to be in school as long as I have! (I pledge my head to clearer thinking…)

“I am incredibly loyal to my family and friends, and to my work and the institutions I represent. I think as a former 4-H’er, it is important to represent the institution of 4-H and Cooperative Extension. In the times that I have worked with Cooperative Extension, I have felt that much more pride in the work I was doing as a product of the Cooperative Extension system. (my heart to greater loyalty…)

“I have more or less dedicated my life to service. For example, I served as an AmeriCorps member helping others learn to grow food in our country. I also attempt to help others produce food in a sustainable way internationally, as well. (my hands to larger service…)

“This also connects to the idea of better health, as I believe strongly in living a happy and healthy life, and so much of that is relevant to sustainable agriculture and helping others to grow their own food (my health to better living).

“I had no idea as a child that the pledge would become so true for me later, as I continue to make my community, my county and my world a better place.”