As a child in the 1960s, Lonnette Marsh grew up in South Carolina with an appreciation for farming and a passion for sewing. Her experience on her family’s farm provided many life lessons, which she was able to apply to her life beyond the land.“

I appreciate the knowledge and experiences that I had growing up on a farm,” she explains, “but fortunately, my parents also stressed the importance of education.

”Her experience working “sun-up to sundown” alongside her family taught her the value of hard work, which she has carried with her throughout her career, leading to her current role as Western Regional Extension* Director at North Carolina A&T State University.

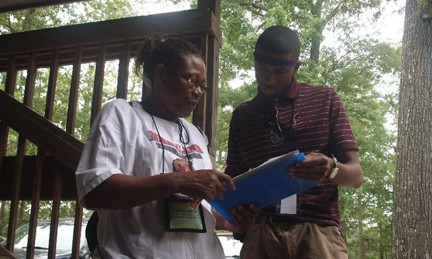

During our conversation, Marsh described her farming experiences, shared how her father’s passing shaped the course of her education, and explained how she is hoping to expand learning and leadership opportunities to minority youth today.Please describe your 4-H experience and where it began.

Lonnette Marsh (LM): My 4-H experience began when I was in the 4th grade, in Chesterfield, South Carolina. We had monthly meetings which were split between girls and boys; my fondest memories are of my sewing projects.

Were there any stand-out skills that you learned during 4-H, or skills you learned from a mentor, that became the foundation of where you are today?

LM: My 4-H sewing projects stuck with me, so I took Home Economics classes in high school. I later followed that track, majoring in clothing and textiles—now called fashion merchandising—at North Carolina A&T. After doing an internship in retail, though, I realized that wasn’t the field for me.

My 4-H Extension Agent was a mentor to me. She seemed to have it all together, and I aspired to be like her growing up. She instilled in us the value of manners, as well as how to carry ourselves, how to present ourselves, and how to walk appropriately; skills that you need as a young female. Both my parents were also great role models.

How did your experience and interest in Home Economics and sewing lead you to Extension?

LM: Two of my instructors at A&T encouraged me to consider Extension as a career. North Carolina Extension was not hiring, so I applied for a position in Virginia. That’s where I started my career – as a 4-H Agent in Bedford in 1988. That’s also where I learned about all aspects of Cooperative Extension*, including 4-H Youth Development, which was called Home Economics at the time. After 23 years with Virginia Cooperative Extension, ending as the Central District Director, I moved back to North Carolina in 2011.

Were there any obstacles that you faced along the way to get to where you are today?

LM: I don’t consider them obstacles; I like to think of them as opportunities. During my senior year at A&T, my mother became sick and my father passed away a month before I graduated. While this slightly changed some of my plans, it did not deter me from getting my master’s degree in home economics and continuing my Cooperative Extension career.

In fact, my father’s death and my mother’s sickness helped me to understand that if I could get through what I thought was a life-ending situation, then I could get through anything. Whenever I’ve come up against a challenge or an opportunity, I’ve thought back to how I felt then and used that to encourage myself to go on.

Do you think that there was an expectation from your parents to pursue farming full-time as a career?

LM: They just wanted my sister and me to get an education. However, my father also wanted to leave us our family land, which we were to either farm or build on. My sister and I still own that land. I plant and harvest trees on my portion, which makes me a small farmer.

I want to get your perspective on 1890 land grant universities**. Can you share with me how these universities are continuing to open doors for students and expanding knowledge in the community, whether it’s in ag or other areas?

LM: The concern many of the 1890 land grant universities face today is ag literacy. We are having to help young people, and even older people, understand today’s agriculture. This isn’t just limited to 1890s, but it seems that much more difficult for those universities. As a result, we collaborate and create new ways to attract students and help them understand the value offered through agriculture programs. Once we get them to see that ag is the foundation, it becomes a little easier to steer them towards these majors. Additionally, as 1890s we are looking at ways to get young people interested in production agriculture, including helping them to see how technology plays a key role in today’s farming. Even in Cooperative Extension we play a key role in ag literacy. If we can get the young people in 4-H, we can help them see the wide array of opportunities that exist.

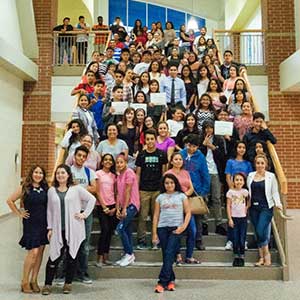

Can you share how you think schools and other youth organizations like 4-H can continue to encourage diversity and inclusion, and empower young people to seek out or follow a path that will result in a leadership opportunity?

LM: I think it needs to start in elementary school. Even at this age, there are leadership opportunities in the classrooms. Youth can become line leaders or lead a project. Schools can also invite speakers or plan career fairs so students will learn about the opportunities that are available to them. Other options can include job shadowing opportunities and college campus visits. They all expose students to various types of leadership roles.

Lastly, what is your vision for the next generation of leaders?

LM: Ironically, my vision is the vision of my alma mater, NC A&T: “North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University is a preeminent land grant institution where high-achieving scholars are engaged in transformative teaching and learning, civic outreach, interdisciplinary research and innovative solutions to global challenges.” And part of the responsibility of getting students ready for A&T, or any other institution of higher learning, is the work, the experiences and opportunities offered by 4-H.